From the Steve Drassler Collection

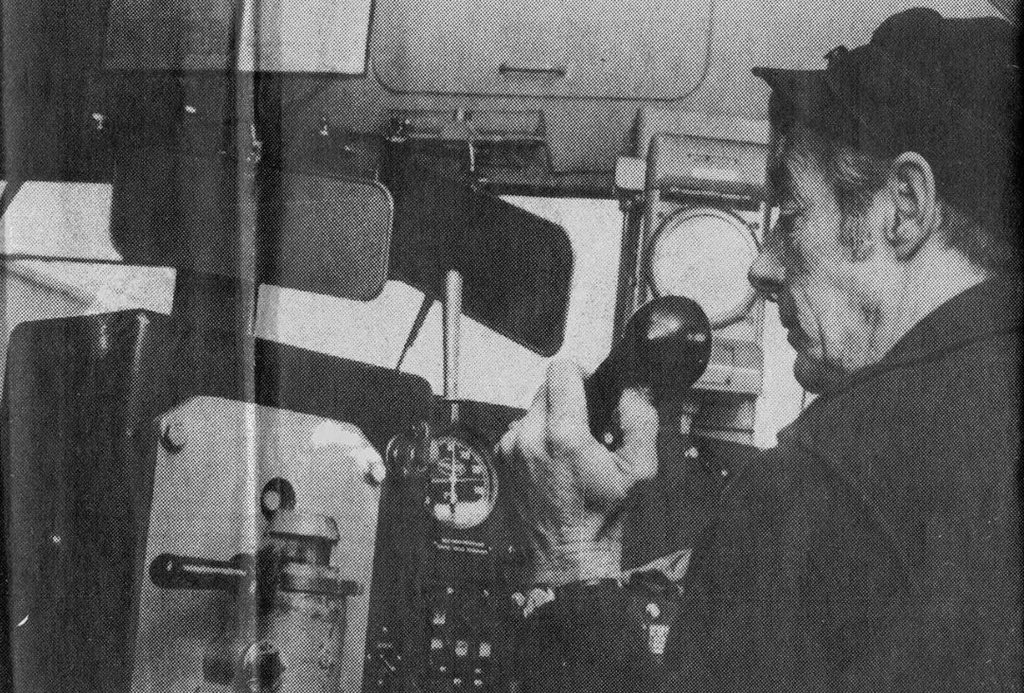

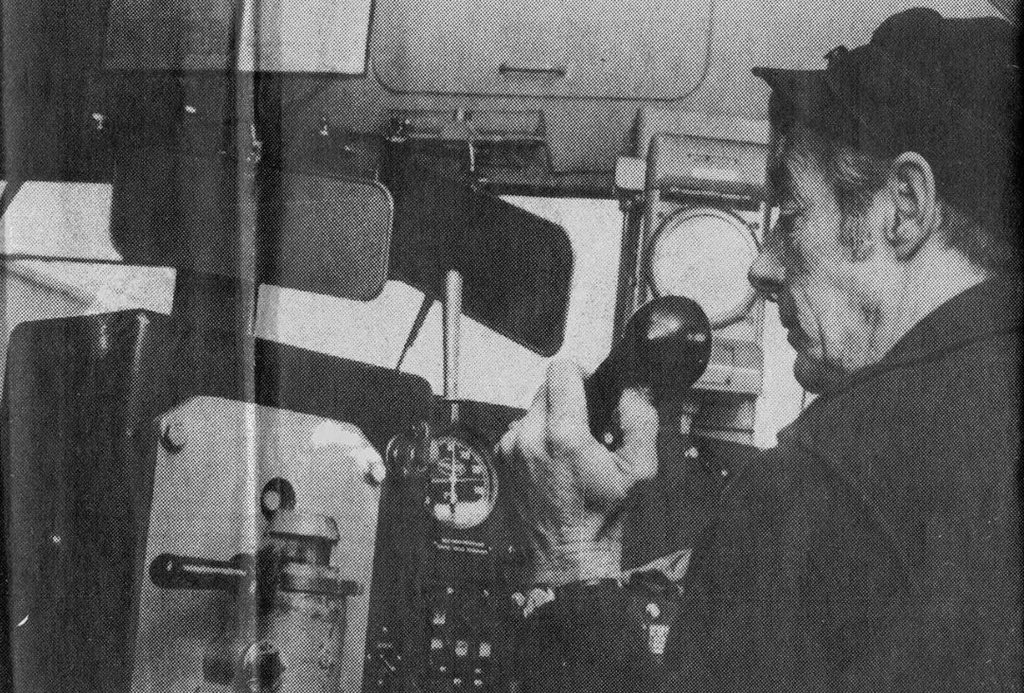

Engineer Fleming Has Served His Time On The Rails

By Richard McNeill

Times Staff Writer

The pre-dawn quiet over Ship Creek Valley breaks with the high, mournful whistle of an engineer nursing a string of freight cars across the yard.

A long shuffle of fuel, pipeline supplies, autos and auto parts from one track to another begins. The yardmen signal, the cars nudge into position and lock with a clash of metal on metal. The day begins.

With a yawn, with ham and eggs and coffee and with fresh puzzlement over his tax returns, the day also begins for senior man at the yards, engineer Pete Fleming.

It is his train the yardmen are pushing and pulling together, While Fleming sips his coffee the yardmen build from the confusion of the yards a strong of freight cars marked for points north.

Fleming knows the routine. He’s served his time there. He served his time on the Alaska Railroad since they stoked steam engines with coal and filled water tanks at stops along the route.

He served his time the day he took an old 500 series steam engine over the hills to Healy with a man named Otis, who was then his engineer. Fleming was a fireman then throwing coals into a red hot stove.

“The only place on that whole engine that was warm was in front of that fireplace,” Fleming said.

“When we got to Healy it was 45 below.”

And they sent the train on.

“We had a hot load” of fuel Fairbanks was in desperate need of it.

Past Healy, on to Brown, Otis took his train and with each mile further north, it got colder. Brown was a water stop.

Fleming rigged the water chute to the tank, struggled with the icy valve and filled it.

“Is that tank full?” asked Otis.

“Yes,” Fleming replied.

“I’ll bet I can get another 100 gallons in there,” Otis said. He took over the water trough to prove his point.

Ken Frauley, a brakeman, was checking the brake box below, Fleming was standing by, Otis was pouring water till it met the brim, passed the brim, overflowed.

“He got sopping wet,” said Fleming. “Not only him, we all got wet.”

Frauley beat the others in a race to the front of the fireplace in the cab and was standing there when Fleming crawled in.

“Frauley,” cried Fleming, “you’re on fire.”

“No I’m not. That’s steam.”

“He took a swipe at his backside with his hand and the whole seat fell out.”

“Cold as I was,” said Fleming, “I laughed and I laughed.” There he was with his bum hanging out.”

Otis came in and in dead earnest quipped, “It’s so cold the water on my knee cap is froze.”

Fleming had another laugh.

And a few hours later, when they at last made it to Fairbanks, the others had a laugh. Fleming took off his boot and its linings and discovered that water had seeped in.

“The whole bottom of my foot came off.”

“It was a miserable trip.”

That was 1948.

It was January 1975, when Fleming sipped his coffee and figured his income for the year passed.

He had plenty of time to kill before the yardmen would finish compiling his train and the stationmaster would ring his home.

At 2:30 p.m., the call came. Fleming checked to be sure his bib overalls were in his pickup truck, he pulled on his wool cap, and wheeled from the driveway at 234 W. Manor St. and headed for the freight yard.

Once there, he walked through the snow to the yard office dodging freight cars that were still being shuffled around.

“Every day before reporting for duty we have a time check. Everybody’s supposed to synchronize their watches.”

The exact time is marked by a wall clock. He signs in on a register and makes note of track conditions and railroad traffic on a posted train bulletin.

“This is probably about the poorest time of the year,” he said. “A lot of frost heaves raise the tracks.”

Fleming will pass rail crews later in the day easing the heaves out of the track with shims. Since the crews cannot cut the heaves away, they simply make the bump gradual by placing wooden slats, or shims between the rail and the rail ties.

Fleming’s train will coast over them slowly, nevertheless.

His train will also pass oil cans belching smoke and fire alongside the track. These are to melt down glaciering deposits near mountain streams.

“This year we have more glacier buildup than I can ever remember,” said Fleming. There’s often notice of it in the bulletin.

Fleming’s next stop in the Anchorage yard is the train, itself; a 3,000 series class monster with a cabin about six feet long and an engine ten ties longer. The series number denotes horsepower.

“We go up,” said Fleming, “and get on our motor power” preparing for the first of three brake tests. The brakeman in the caboose radios to Fleming who sits in the drivers seat. “Set the brakes,” he says.

Fleming first reaches to a metal handle about four inches long which is just about even with his left shoulder. He pulls it once, long. The whistle, even from the cab, sounds likes a drifting, mournful song. Then he sets the brake with another lever.

The air brake system is checked for leaks and the brakeman radios to release them.

Fleming pulls the whistle twice.

They’re ready for a roll-by.

Art Reekie, the conductor, takes his seat at the other side of the cab while the two brakemen, Bill Shake and Bob Lucas, stand in the snow checking wheels and brakes as the train slowly passes them for inspection.

Herb Worthely, the fireman, makes his final check.

The crew, then, is all aboard.

Creeping out of the yard at 10 miles per hour, they get under way, blowing the whistle again and again at the crossing. It’s two long blasts, a short and a long at each road.

Finally, outside of town, at Mile 117, they put on speed to 25 miles per hour pushing the throttle open just a little more. There’s plenty speed yet to come.

If there’s trouble on the track - and there’s none this day - Shake, the brakeman, gets cold.

“He has to go out and protect the train,” said Fleming.

He brings fuses, a red flag and “torpedoes,” explosive devices which clamp onto the track and will explode with the sound of a gunshot if hit by a train.

When an engineer hears two torpedoes go off, he knows he has to stop his freight or passenger train within a mile.

Shake sits in the caboose and gets the word of trouble over the intercom. But there’s also a whistle.

“One long blast and three shorts will send him out and four longs will bring him back in.”

When the problem’s repaired, the conductor gives the go-ahead.

There’s another spot check and roll-by to check the brakes at Willow, and then full steam for Curry and a hot meal before they tackle “the hill.”

Curry is a World War II army office building converted to a mess hall and quarters for railroad cooks Leon and Alice Ericsson. There’s only one good way to get there: train.

Leon and Alice are “real nice people. If you get spaghetti today, you won’t get it tomorrow.”

The menu’s not always pasta, either. The Ericksons serve up roasts, steaks, chicken and full meals for a railroad man’s appetite.

Curry is 134 miles from Anchorage and just 100 miles shy of the end of the run at Healy. The only thing standing between them and home base is the Talkeetna range and a few moose.

The range comes first. The train builds up speed with about five engines pulling an average string of some 60 to 75 cars with a gross weight of 4,000 tons of freight. It hits the grade at Chulitna Pass and Fleming gives it all the power he’s got.

Of course he makes it. He does it every day he rides that stretch of rail.

But Fleming has to admit there was a day not too long ago “I never thought I’d see a train of 90 cars go up that hill.” Now, it happens.

Just before the Talkeetna “hump,” the train pulls in to Hurricane. “The rear (caboose) brakeman will ride in front until Hurricane where he jumps out as Fleming slows to about 10 miles per hour.

As the train rolls by, the brakeman checks the loads and air hoses. Then, because the train’s still rolling, he grabs a handle on the caboose before it leaves him standing there.

The roll-by is completed without stopping.

After the 2,363-foot “hump” it’s all downhill to Healy…if only the moose don’t get in the way.

“I've probably hit a dozen,” said Fleming.

“They’ll see that bright light coming and break their necks to get on the track.” The moose know they can run on the tracks better than they can on the snow. But they don’t know a train’s not going to chase them out into the meadow.

“This year we haven’t seen a moose on the track. That highway has taken a lot of pressure off.” Fleming believes the moose are keeping their distance now because of auto traffic on the road which parallels the rails.

In years before, though, “I’ve run moose as much as 12 miles down the track.”

The moose - in the days when a train could stop in time to avoid hitting it - would run ahead of a train down the track rather than jump off into the snow.

“We’d have a guy waiting at the next station to scare them off.”

Some would turn and attack.

“I’ve seen one hit that old plow, back up and roll its head around a few times.” Fleming smiled, remembering.

Today there’s not even time for a moose to charge; not when a train’s doing 45 miles per hour and rounds a corner surprising one.

“What seems to work,” in a case like that, said Fleming, “Is you get right up on top of them and blow the whistle. Sometimes they jump.”

“Dogs,” said Fleming, “are the dumbest. They’ll run, too. Sometimes you see a rabbit, wolf, fox…A bear will normally get off the track all right.”

And the train rolls into Healy. Fleming signs in, he “ties up for a legal rest,” with a cup of coffee and a hamburger, and gets some sleep before he slides into the engineer’s seat for another freight home.

“It’s both adventure and job,” Fleming said.

“I like railroading.”

Page created 5/5/16 and last updated 5/5/16